Ocean Currents

The water doesn’t stand still but is in constant motion as currents around the globe. At the same time, it transports heat, salt, nutrients, organisms and objects, for example.

Several factors move the water. Winds drive the surface water. The shapes of the seabed and coasts affect the direction in which the water flows. Flows driven by density differences are also called thermohaline circulation. Cold and saline water is denser than warm and fresh. The water masses tend to settle according to their density, that is, the denser under the lighter, which causes the water to flow. In general, from warm areas, water flows near the surface to cooler areas, from which cool water flows back near the bottom.

Currents transport heat

The atmosphere gives heat to the sea surface layer, and the currents of the oceans transport the heat in the oceans. Some examples of warm ocean currents are the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic and the Kuroshio in the Pacific Ocean. Kuroshio transports heat along the coasts of China and Japan to the north.

Cold currents are opposite to the warm currents. For example, the cold Labrador Current flows between the Gulf Stream and the continent of North America and prevents the warm water of the Gulf Stream reaching for example the eastern coast of Canada. The cold current opposing Kuroshio in the Pacific Ocean is called Ojashio. Thus, ocean currents even out the differences in temperature between the Earth’s regions.

Land areas by cold ocean currents are usually drier, and areas near warm currents usually moister. This is due to high evaporation rates by the warm currents, thus increasing rainfall in the land areas nearby. In turn the moistness by the cold currents condenses already at the ocean and rains down there. This is why there’s often deserts by the cold currents, such as the Atacama Desert by the Peru Current (also known as the Humboldt Current).

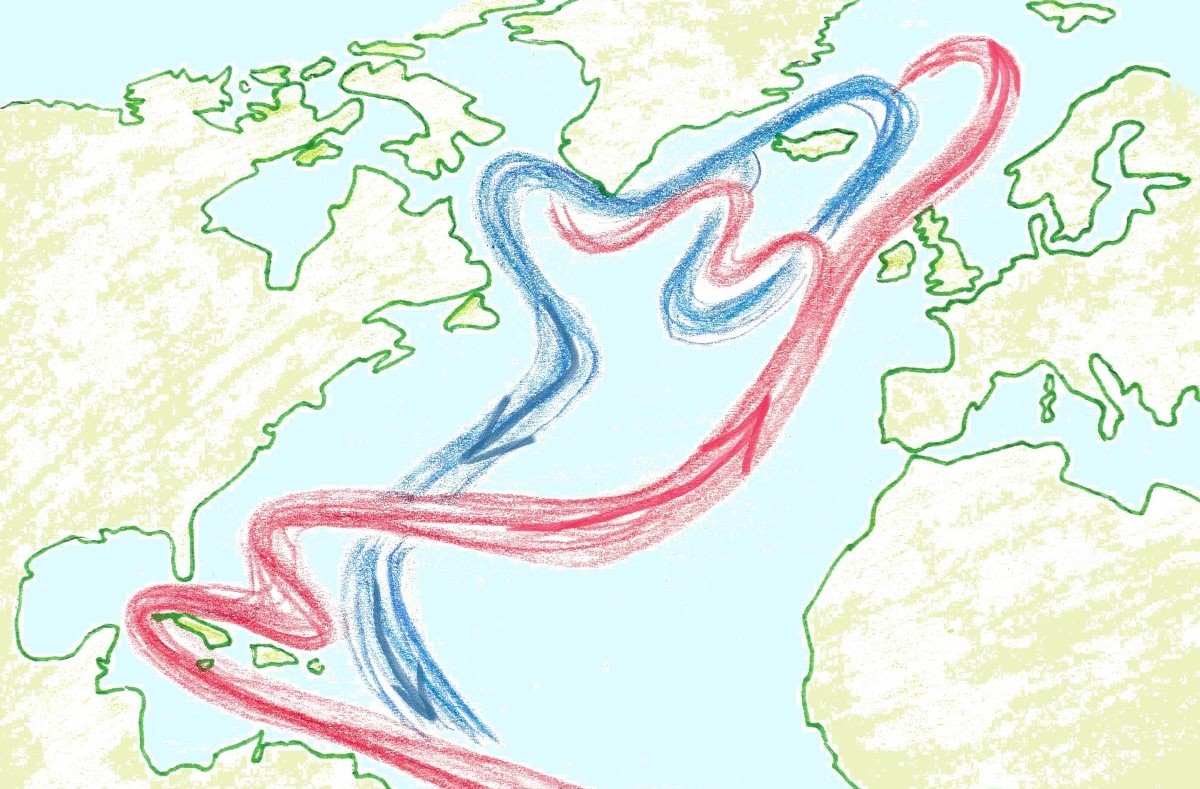

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation – AMOC

Finland's climate is most affected by the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation abbreviated as AMOC. It is driven by wind and differences in water density. The surface water near the equator is warm and flows north. Meanwhile it releases heat to the atmosphere and thus becomes denser, causing it to sink towards the bottom. Correspondingly, cold seawater from the north flows south close to the bottom.

The most significant warm ocean currents of AMOC are the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Current. The Gulf Stream starts from the warm Caribbean Sea, transports warm water northeastwards along the coast of North America, and continues as the North Atlantic Current further north towards northern Europe. Because of this, northern Europe is warmer than other countries at the same latitudes, such as Canada. In contrast, the Arctic Ocean sea water is cold and that´s why denser and flows southwards deeper in the ocean.

Because of the climate change, the surface water flowing to the north does not lose as much heat on the way as before. Also more fresh water, that is less dense than saline water, is mixed in it. As a result, AMOC is predicted to weaken. Forecasts have also considered the possibility of a rapid slowdown of AMOC, but for the moment it does not seem likely.

8.7.2025